SSL Doesn't mean secure

Holy bait-title Batman. Okay, I'll hold my hands up and say that the first word in SSL is literally the word "Secure", so what I'm actually saying is that SSL alone doesn't mean security.

Security is one of the four pillars that we promote at Sonassi; we are huge advocates in educating merchants as to the merits and importance of online security.

There are two particular aspects to online security, where the two are not actually connected,

- What a consumer sees when they visit a website to determine it is legitimate, safe and secure

- What a merchant is doing to prove their legitimacy, safety and security

But a sudden change in Google Chrome 69 introduced an "experiment", the removal of the business identity shown when a website possesses an EV (extended validation) certificate. I took to Twitter to voice my frustration to be met with some challenging responses from some extremely capable security experts, all of which I have a huge amount of respect for - but incidentally disagree with.

Types of SSL certificates

So the discussion started with the various types of SSL certificates available to online stores;

Domain Validation (DV)

These are verified using only the domain name, typically via email, DNS or HTTP verification file.

Organisation Validation (OV)

These require more validation than DV certificates, but provide better identity verification. The certificate authority will verify the existence of the business that is attempting to get the certificate. The organisation's name is also listed in the certificate, providing a means to verify identity of the certificate owner.

Extended Validation (EV)

This certificate provides the maximum amount of identity verification (for an SSL certificate), and require the most effort by the CA to verify. Extra documentation must be provided to issue an EV certificate, and like the OV, the EV lists the company name in the certificate itself. However, where an EV certificate differs is that the web browser will actually show the company name in the URL itself.

So what changed?

In Chrome 69, the display of EV certificates has changed - or more specifically, gone. There's a Google Chrome experiment underfoot which makes an EV certificate appear as no more than a DV certificate.

Where an EV certificate would once have shown the company name the certificate was issued to, this new update removes that. Which, in my opinion, has removed a form of identity verification that I truly value as a consumer.

When you are browsing websites online, something that is key, if you are providing personally identifiable information, is that the site you are browsing is legitimate, trustworthy, safe and secure. But this is an incredibly difficult thing to determine. So as a consumer, you become reliant on trust and identity markers that allow you to make a judgement.

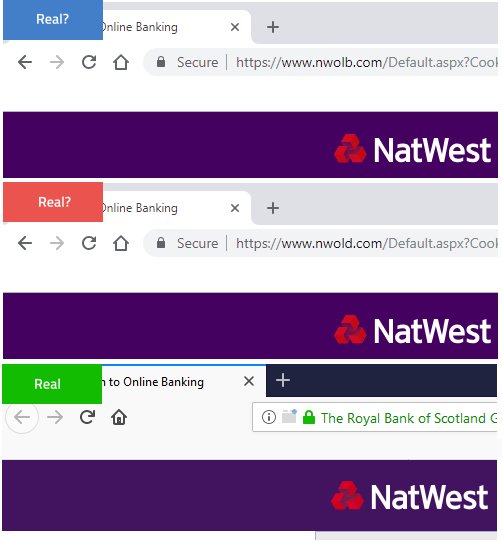

Here's a real world example with an online bank.

There's two elements to check when you land on a page like this,

- Is it legitimate?

- Is it safe?

Legitimacy could be determined by checking the URL is correct, where Scott wrote a compelling article on techniques to achieve this, it still remains that humans are prone to error and this alone isn't enough.

Look for the padlock. That's what we've been trained to do after all. But whilst this confirms the transport layer between you and the server you've reached (read: the first server, read on) is secure - it by no means means the site itself is legitimate. Fraudsters can just as easily obtain a DV certificate as a legitimate business - there's no barrier to obtaining one.

Look for the "green bar" and company name. This is the key identifier of an EV certificate; where it confirms that the site you are looking at belongs to the company shown in the green bar. In the example above, any Natwest customer would know they are part of the Royal Bank of Scotland Group. They key here is that whilst a consumer may not know whats involved to procure an EV certificate, it remains that it is not possible for a fraudster to obtain an EV certificate with the identity of another business.

Do EV certificates imply trust, or security, or identity?

This is the debate. There are many articles online advocating the merits of EV certificates; case-studies of improved conversion, customer confidence etc. - but Sonassi has always had a neutral position regarding this. Do your own research, form your own opinion.

The heart of an EV certificate is that it does one thing, it helps consumers by performing that very first step of identity verification, to show the company that it had been issued to. This initial vetting can allow a consumer to cut down the amount of time it takes to verify that they have reached the right website.

I don't believe that EV's are technically any more secure; or that they were ever meant as a de-facto standard for implying security, or trust. The goal of this type of certificate was to offer consumers a fast way to verify the identity of who the certificate was issued to - and it did it in a highly effective way. But now that Google Chrome is set to remove it - its now made that verification step a lot more difficult. By making an EV no better than a DV; there's no instant way of knowing whether that innocent typo of reaching www.nwolb.com or www.nwold.com actually landed you on the right site, or the wrong site.

Obtaining a SSL certificate

DV Certificate

It is now easier than ever to obtain an SSL certificate; with the likes of CloudFlare offering free, instant SSL and the amazing Let's Encrypt project doing the same. All you need to do is register a domain name, go through an instant verification process that needs nothing more than a DNS record or verification file to be present and you've got an SSL certificate. It automatically renews and you can completely forget about it - security solved.

EV Certificate

Whilst the average consumer might not know this; the process to obtain an EV certificate is a lot more involved than the above, typical steps to procure an EV look like this,

- A signed copy of the EV Subscriber agreement

- A signed copy of the EV Authorisation Form

- Submission of one of the following

- Your company’s Dun & Bradstreet number

- A letter from a Certified Public Accountant to verify your business

- A letter registering a legal opinion, or a letter from a Latin Notary, to confirm your EV request.

- (For government entities only) A legal opinion letter verifying a government organisation

Then, after submitting the above, the certificate authority will then

- Verify Legal Existence and Identity by verifying the organisation registration directly with the incorporating or registration agency.

- Verify Trade/Assumed Name (if necessary)- this is only applicable if the company does business under a name which is different from the official name of their corporation. The company's trade name must be registered and verifiable.

- Verify Operational Existence – typically this means confirming that the company has a current active demand deposit account with a regulated financial institution to verify that the company is able to conduct business operations.

- Verify Physical Existence through the company’s address and organisation phone number.

- Verify Domain Ownership via a WHOIS search.

- Verify the name, title, authority and signature of the person(s) involved in requesting the certificate and agreeing to the terms and conditions.

Comparing DV to EV procurement

So for a DV certificate - it requires zero time, zero expense and zero effort to make a site "secure" - but for an EV certificate, there's a thorough vetting process - so when you land on a site, you know that someone has at least made some effort to verify the legitimacy of the company that operates the website.

Consumers don't have to exclusively rely on this to form a trust relationship - that's not the purpose of an EV certificate. But what they do have, is that little bit more trust that the identity of the site they are on, is in fact the company they expect it to be.

EV certificates are a trust marker, one piece in the difficult puzzle that consumers can use to verify they are on a legitimate site.

But for DV certificates, it is possible that within seconds of buying a domain name, a company can have a "secure" website - and here within lies the issue; they don't have a secure website at all.

But savings on EV certs. mean more invested elsewhere

In my experience, it doesn't. When any business sees an opportunity to make a cost saving in one category of a budget, they do not then look to maximise that remaining balance elsewhere. If anything, its a trigger to then see if there are other free solutions to other security investments being made. It often needs a price to go with a product, for it to be valued - take that price away and of a sudden, security has no more value.

So in Google advocating the end of EV certificates; they are effectively, like it or not, telling merchants not to invest extra money or effort in security.

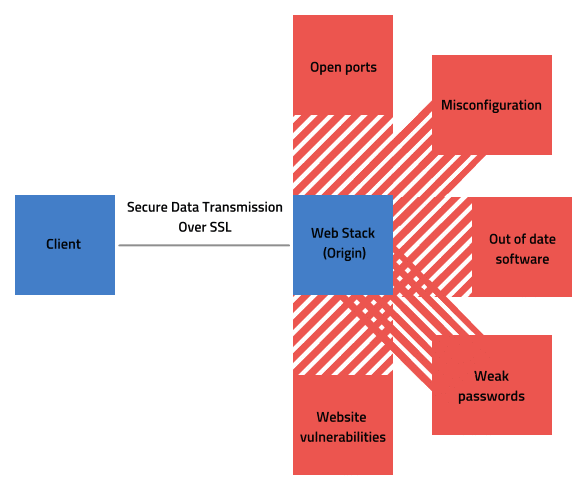

When is SSL not actually secure

Here's the key issue; that SSL is a tiny, little piece of the wider security puzzle of securing an online business - but not everyone is a security expert and there's a problem where merchants and consumers conflate the security of the transport layer, with that of the entire business.

The CloudFlare effect

Firstly, let me say that I'm a huge lover of CloudFlare - both product and company. The technical achievements they have made are amazing and its a truly impressive product that we're happy to endorse here at Sonassi. This problem isn't just restricted to CloudFlare, but any hosted SSL proxy service that doesn't enforce origin checks.

Unfortunately, it is entirely possible to abuse and misuse CloudFlare, not because of any malicious intent, but simply because the user setting it up doesn't know better (or they have read a guide online advocating that it alone adds security).

There's two ways to configure CloudFlare, one is by enabling SSL on both CloudFlare itself and on the origin (your web stack) - which means the data stream is encrypted from user to origin. This requires installing/enabling SSL on both environments.

But all too often, CloudFlare is deployed in "Flexible" mode - where it isn't reliant on the origin having an SSL certificate installed. This means whilst the data is secure up until it hits CloudFlare, it isn't as it transits the internet to the origin. Not only is this not secure - but it is also deceiving the consumer into believing it is.

When the origin isn't secure

The wider issue that simply hasn't been discussed is the fact that SSL alone means nothing. It is far more difficult to craft an attack that intercepts unencrypted data between client and server - than it is to just target the server itself; which is why SSL is barely a fraction of the piece of the security puzzle.

Its entirely possible for the data to be secure from client to stack - but the stack itself is a giant security hole, with exposed ports to the internet, out of date applications, weak passwords, misconfigured settings or worse.

Put simply, installing an SSL certificate barely covers a fraction of the surface area for attack. It is definitely required, but you shouldn't stop there.

Coming full circle

So this is where the discussion really comes down to what Google Chrome originally did. When I think of the uneducated on the internet, those that need help, I typically think of my parents (fortunately, I know they don't read our blog!). So when I ask my parents how do they know a website is secure - their single answer is "it has the padlock".

"It has the padlock"

As more services move online, as more consumers turn to the internet to carry out their day-to-day needs, consumer vigilance needs to be at an all time high - and the lessor experienced consumers rely almost exclusively on trust markers they have been taught and indoctrinated to look for.

Like it or not, in the eyes of the non-technical, the padlock has become the defacto standard for marking a site as secure, safe and trustworthy. The browser industry really needs to take a long hard look at how powerful their influence is over consumer's judgement of the security of a website.

Instead of removing helpful trust markers like what EV certificates offered, they shouldn't be moving backwards in stripping away trust markers, but advocating them and integrating more. In my opinion, the padlock should be comprised of a number of factors,

- PCI status of a website

- EV verification

- ASV report scores

- Etc.

The URL should offer more trust markers, not fewer - and what Chrome has done (for now) has made it that bit harder to verify the identity of the company of the website they are viewing.